From The Journal of The Bahamas Historical Society November 2018

Article by Kelly Delancy

Cholera, typhoid and yellow fever were among the most deadly known diseases to threaten the wellbeing of the nineteenth century Bahamas. These and other infectious diseases spread quickly from shore to shore with the increase in movement and migration during the Age of Sail. New Providence was particularly vulnerable to the spread and incubation of infectious disease due to its popularity among foreign visitors, its use as the central market for Out-Islanders, and the often crowded, unsanitary living conditions.

The Bahamas experienced its first epidemic in 1852-1853 after the bacterium, Vibrio cholera, gained passage to Nassau on the Bahamian vessel, Reform, which had sailed from New York2. At the height of the epidemic, New Providence experienced 70 cholera deaths per week. The disease then spread to the far reaches of the colony. The death toll included 696 in Nassau, 178 in Harbour Island, approximately 200 in the remainder of Eleuthera, 108 in Abaco, and 40 in Ragged Island 3. The cholera outbreak was followed by a series of yellow fever outbreaks.

Legislation was passed in 1856 authorising the establishment of the Athol Island Quarantine Station in response to the scourge of epidemic disease introduced to the colony by ill passengers on board vessels travelling to and through the Bahama Islands. The construction of this quarantine station followed the passing of several quarantine laws in the mid-nineteenth century. As early as 1845, legislation required that “all vessels arriving at the port of Nassau, together with all persons, goods, and merchandise whatsoever…coming from any port or place where any contagious or malignant disorder shall exist … [shall] be liable to perform quarantine”4. Any ship without a bill of health from its port of departure was to be treated as a ship arriving from an infected port.

Nassau harbour pilots were responsible for inquiring as to the origin of ships from the ship masters and identifying whether the incoming ship was sailing from an infected port. If it was found that an incoming vessel was sailing from an infected port, carrying ill passengers or had experienced a death as a result of disease, the vessel was to be quarantined for two to fourteen days. If any other passengers became ill during this time, the ship would remain in quarantine for an additional fourteen days or until the sickness ceased5. While in quarantine, these ships were required to hoist a yellow flag during the day or a national ensign of the ship at half mast, and a quarantine light at night signifying its infected or suspected status. Once cleared by the health officer, the ship would receive a certificate and be free to continue on to any port in The Bahamas6.

Prior to the construction of the Athol Island Quarantine Station, infected vessels were permitted to quarantine at an anchorage at Salt Cay, Rose Island or Athol Island. The 1871 Quarantine Act established the quarantine station at Athol Island as the exclusive quarantine location for Nassau. The south side of the island was identified by the Chief Civil Engineer, Thomas C. Harvey, as most suitable for the quarantine station because it was dry, free from swamps and rose to a height of 30 feet above sea level. The island also contained fresh water wells and soil suitable for fruit trees7.

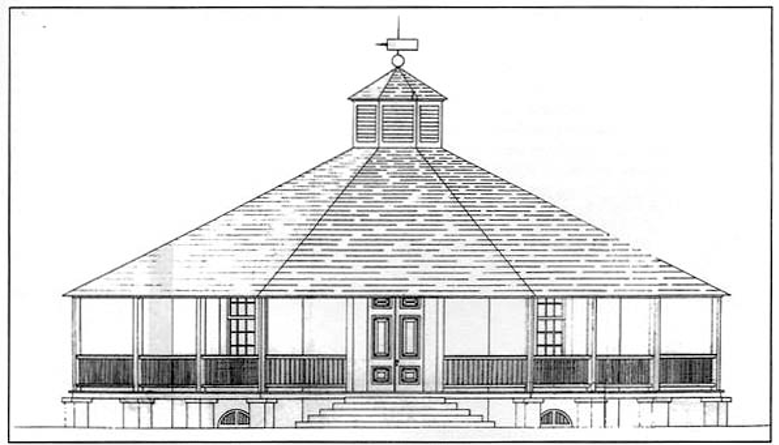

The quarantine complex was unique in its architectural form and features. The station took the form of four detached octagonal buildings made from local limestone rocks bonded together and plastered with locally made lime plaster. The design represents a rationalist approach to institutional building popularized during the Victorian era (1837-1901) by American architect, Orson S. Fowler. The octagonal form was believed to better withstand storms and promote ventilation. The quarantine station complex included an octagonal convalescent hospital surrounded by open verandas, an octagonal kitchen building, an octagonal main hospital building, an octagonal quarantine officer’s dwelling, and subsidiary buildings. Vessels would dock at the wharf on the island’s south side to supply medical staff, patients and visitors.

With the presence of a dedicated quarantine station, infected persons and those suspected to have been in contact with disease had the option of completing quarantine on board the ship, at the discretion of the ship’s master and health officer, or in the quarantine station. At the station, the quarantine officer would hoist a yellow flag to signify that persons were detained therein. Persons in quarantine were not permitted to leave their ship or the station until discharged by the health officer.

The Athol Island Quarantine Station was operational until 1929 when the complex was severely damaged by a hurricane and subsequently abandoned. A 2004 archaeological survey revealed that elements of the station still survive. Archaeologists identified ruins of the convalescent hospital, kitchen, main hospital, store, physician’s office, keeper’s dwelling, keeper’s kitchen, flagstaff, latrine building, stone jetty and access steps from the original wharf8.

The Athol Island Quarantine Station is significant in that it was the first dedicated quarantine complex in The Bahamas and in the Caribbean9. It was among Nassau’s most important public buildings and successive colonial governors ensured its good working order as a necessity for good public health. While much of the physical station has become overtaken by surrounding vegetation, its legacy stands in the form of a Bahamian populace descendant from those spared from disease as a result of its existence.

Endnotes

1. [Image] Thomas C. Harvey C.E. Design for Convalescent Hospital at Athol Island. CO23/151:340, August 1856, Department of Archives, Nassau.

2. Craton, Michael and Gail Saunders. Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People, vol. 2. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998:64

3. Ibid.

4. Brooker, Colin. Historic Cultural Resource Reconnaissance of Athol Island. Preliminary Report of Field and Research Activity, April 20-24, 2004 to the AMMC, p.5.

5. Brooker, 2004, 6.

6. Quarantine Act of 1905. Statute Law of The Bahamas, ch. 237.

7. Brooker, 2004, 8.

8. Brooker, 2004, 12-13.

9. Brooker, 2004, 14.

Thanks for the history lesson!