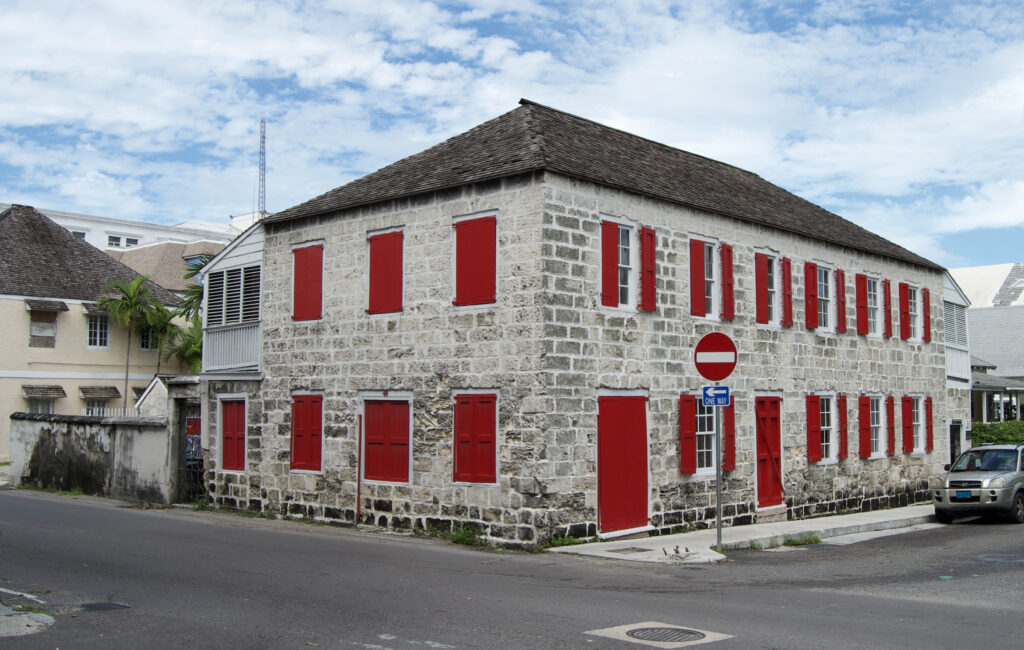

At the northwest corner of the Shirley and Parliament Street intersection, stands a curious stone edifice. The street facades are not decorated. Instead, the original quarried limestone blocks are exposed and their history on full display. The roof is a simple hip with wooden shingles, and windows have flat arches with hinged colonial-style wooden shutters at their sides. The shutters, along with the colonial-style wooden doors, are painted bright red and provide an artful contrast to the uncolored stone building. A wall of wooden louvers is located at the rear of the building rather than front-facing toward the street, in reverse to the typical arrangement. This property, known as Magna Carta Court, dates to the 1780s and is outstanding as its main building and out-buildings are some of the few exposed-stone structures in Nassau. While the structures date to the 1780s, their current look and feel are due in large part to its twentieth-century owner, Edward Dawson Roberts, and his family.

Records indicate that the property was once larger. It was first granted to Robert Duncome, a Loyalist and merchant, in 1789. On February 26, 1802, the property was divided and the southern portion, which is today the Magna Carta Court property, was sold to David Rogers, a cabinet maker.[1] In 1802, David Rogers and his wife Elizabeth sold the property to Aaron Dixon.[2] Dixon had come to The Bahamas from Scotland and established a business on Shirley Street. He died on December 3, 1809, and in his will, he bequeathed the lot to Christ Church. He stipulated that the lot, with all its buildings, be rented and that any profit after maintenance is paid be applied to the education of fatherless children. The property remained in the possession of the vestrymen of Christ Church from 1809 to 1859. In 1859, a special act of the legislature was passed to permit the sale of the property by public auction.[3] At this time, the property required repairs in an amount greater than Dixon’s estate could afford. Vestry of Christ Church auctioned the Magna Carta property at the Vendue House in 1860. It was sold to Sarah Elizabeth Sears Alday, who is described as a widow.[4] When Alday died intestate in 1885, the property went to her six daughters. In 1895, Alday’s daughter, Maria, who was married to Ernest Kingsbury Moore but was then a widow, purchased the interest of her five sisters.[5] Maria Moore operated a commercial bakery on the premises. The bakery was located on the ground floor on the southern end of the building. An old oven remains preserved on the property.

On November 7, 1931, Maria Moore conveyed the property by deed of gift to her son, Walter Kingsbury Moore (later Sir Walter) in trust. The property was occupied by Maria Moore’s two unmarried daughters – Hattie Julia Elizabeth Moore and Olive Rhoda Moore. After the last of the daughters died in 1975, the property was rented as an antique shop for a few years. On May 21, 1979, Sir Walter’s children, Walter Kingsbury Moore, Junior through his company Kingsbury Securities Limited and Winnifred Maude Sands (nee Moore), sold the property to Splendid Investments Limited.[6] It was then transferred to Star Corners Limited and prominent Bahamian lawyer, Edward Dawson Roberts, in 1982.[7] E. Dawson Roberts was the son of James Roberts, a carpenter and boat builder from Hope Town, Abaco. His mother, Hattie Roberts was a direct descendant of Wyannie Malone, one of the first Loyalist settlers at Hope Town.

When E. Dawson Roberts acquired the Magna Carta property in 1982 to house his law office, the buildings were plastered and painted brown. His appreciation for the history and natural beauty of the property led him to restore the buildings. He removed the plaster from the exterior surfaces to expose the cut quarry stones for decorative effect. The interior was also renovated, and the roofs replaced. The buildings were repointed in 2017. It was Roberts who named the property “Magna Carta Court.” Today, the buildings still house the firm of E. Dawson Roberts and Company and remain an eye-catching icon of historic Downtown Nassau.

Article written by Dana Newton, Anea Knowles, and Kelly Fowler.

References:

[1] “Lease and Release”, Registry of Records (Book M. 2), 271-276. Provided in notes by E. Dawson Roberts, courtesy of Lori Lowe.

[2] Ibid., (Book O. 2), 30-37.

[3] On April 30, 1859, an Act was passed “to authorize the church wardens and vestrymen for the time being of the Parish of Christ Church, in the Island of New Providence, to sell and convey a lot of land situate in the Parish of Christ Church, formerly the property of a certain Aaron Dixon, deceased.” Found in Laws of The Bahamas 1859, No. 14, 22 Victoria. Department of Archives, Nassau, Bahamas.

[4] Russell, Nassau’s Historic Buildings, 29.

[5] Ibid., (Book P. 10), 360-393.

[6] Ernest Moore had previously sold his one-third share to his brother Walter K. Moore, Jr.

[7] “Lawyer E. Dawson Roberts Dies Age 85,” Tribune (Nassau, N.P.), April 1, 2012.

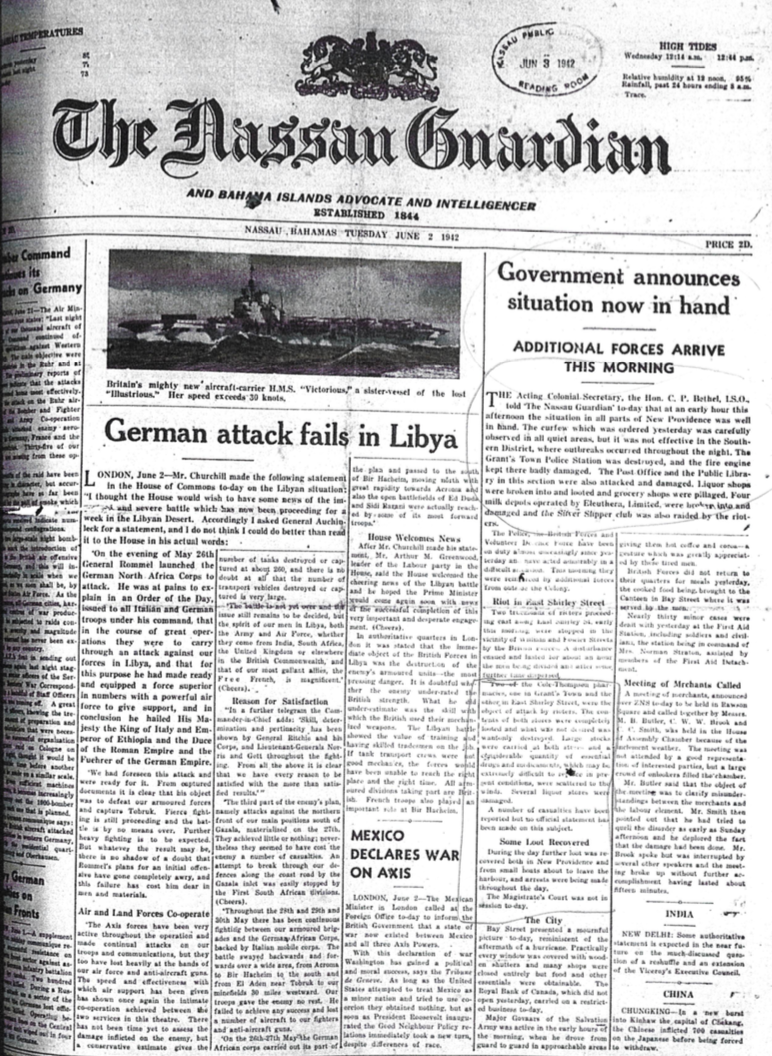

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.