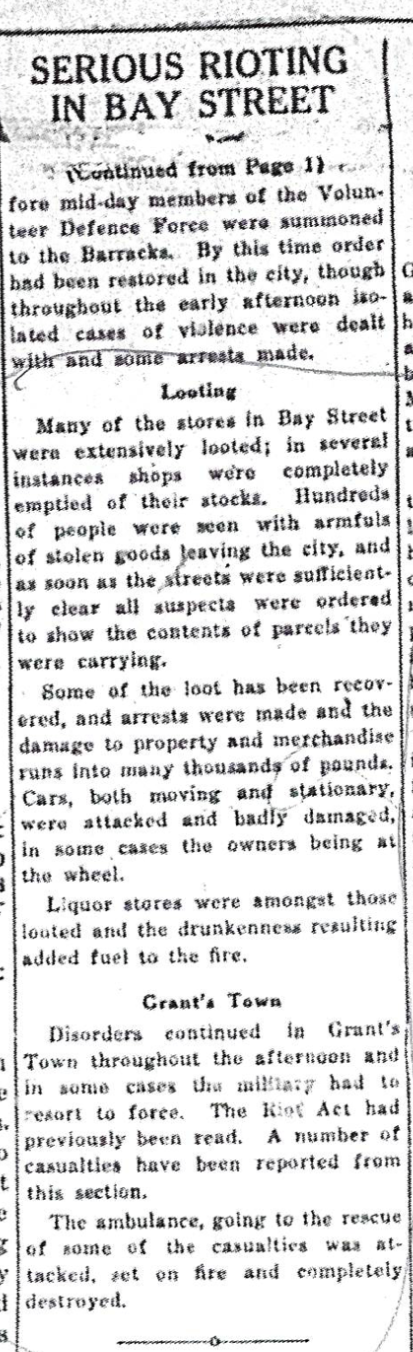

Serious Rioting in Bay Street

SHOPS LOOTED BY UNRULY MOB

DISTURBANCES ORIGINATE FROM WAGE DISPUTE

“Serious Rioting in Bay Street.” Nassau Guardian, June 1, 1942. Pages 1-2.

Bay Street to-day was the scene of a serious disturbance, unprecedented in the history of the Bahamas. Before the riot was quelled, Bay Street presented a picture of devastation, practically every shop window having been smashed and rifled. Not even the Red Cross Centre in George Street escaped the fury of the mob.

The events leading up to the riot were as follows: Yesterday afternoon a party of police, headed by Captain Sears, was called to the scene of a construction project to restore order among a party of workmen who were agitating for higher wages.

The prompt action of the police prevented any further spread of the disorder, but the men went on strike and dispersed.

This incident was followed by a conference last night between representatives of the contractors and the labour leaders. After a lengthy meeting an agreement was reached whereby the workers were to report back to the scene of the construction, pending further conferences. It was thought that the settlement was in sight.

It appears that the workers, however, did not abide by the decisions of their representatives and shortly before nine o clock this morning some hundreds of the workers, followed by a large crowd of hangers-on – including women and children – entered Bay Street via George Street and marched in a reasonably quiet manner up the street until they reached a central point. Between Fredrick and Charlotte Streets, without any apparent warning, the breaking of a single window by an individual was the signal for the general smashing of windows up and down the main thoroughfare.

A Coca Cola truck, parked in the street was set upon and the bottles were used as hand missiles.

While the rioting was at its height a cordon of police with fixed bayonets and steel helmets came down from the barracks and remained standing in formation for some time in front of the Post Office, while the sound of breaking glass and the shouts of the crowd could be heard up and down the street. After a time these policemen moved along Bay Street and were successful in dispersing many of the rioters, who nevertheless re-assembled shortly afterwards in other places.

When it was evident that the police could not cope with the situation a detachment of the British forces were called in and shortly before mid-day members of the Volunteer Defence Force were summoned to the Barracks. By this time order had been restored in the city, though throughout the early afternoon isolated cases of violence were dealt with and some arrests made.

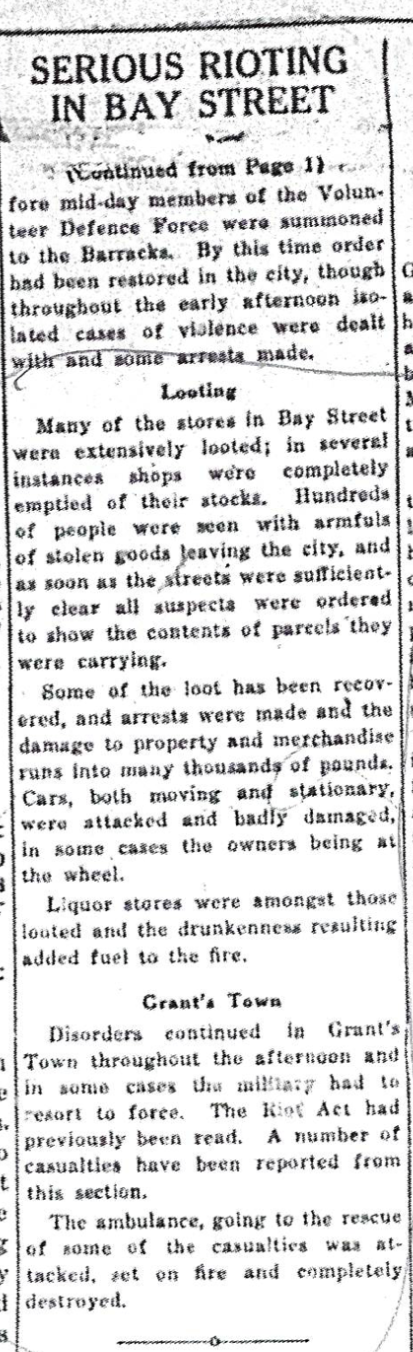

Looting

Many of the stores in Bay Street were extensively looted; in several instances shops were completely emptied of their stocks. Hundreds of people were seen with armfuls of stolen goods leaving the city, and as soon as the streets were sufficiently clear all suspects were ordered to show the contents of parcels they were carrying.

Some of the loot has been recovered, and arrests were made and the damage to property and merchandise runs into many thousands of pounds. Cars, both moving and stationary, were attacked and badly damaged, in some cases the owners being at the wheel.

Liquor stores were amongst those looted and the drunkenness resulting added fuel to the fire.

Grant’s Town

Disorders continued in Grant’s Town throughout the afternoon and in some cases the military had to resort to force. The Riot Act had previously been read. A number of casualties have been reported from this section.

The ambulance, going to the rescue of some of the casualties was attacked, set on fire and completely destroyed.

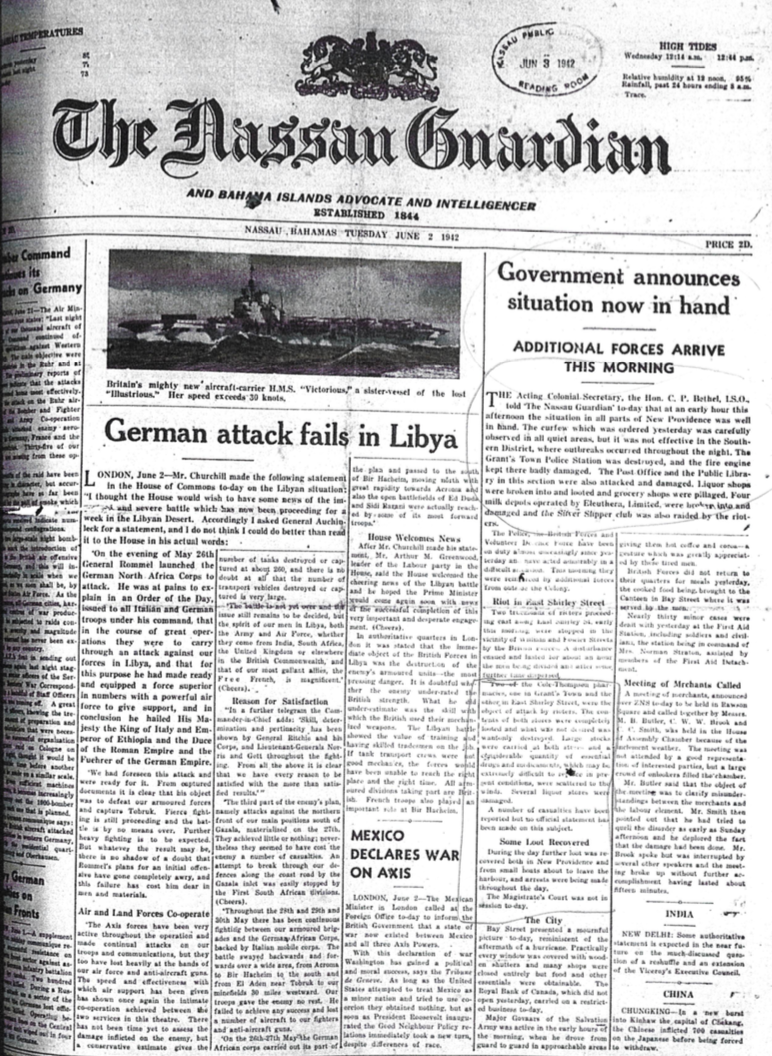

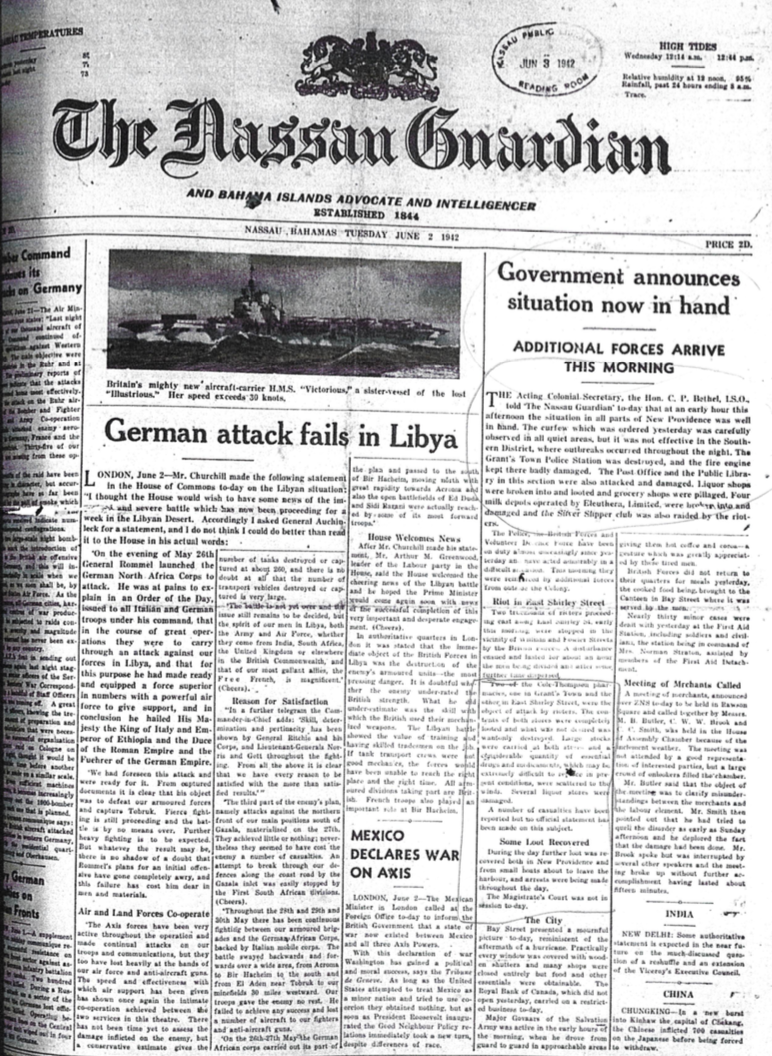

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.

Government announces situation now at hand

ADDITIONAL FORCES ARRIVE THIS MORNING

The Acting Colonial Secretary, the Hon. C.P. Bethel, I.S.O., told ‘The Nassau Guardian’ to-day that at an early hour this afternoon the situation in all parts of New Providence was well in hand. The curfew which was ordered yesterday was carefully observed in all quiet areas, but it was not effective in the Southern District, where outbreaks occurred throughout the night. The Grant’s Town Police Station was destroyed, and the fire engine kept there badly damaged. The Post Office and the Public Library in this section were also attacked and damaged. Liquor shops were broken into and looted and grocery shops were pillaged. Four milk depots operated by Eleuthera, Limited, were broken into and damaged and the Silver Slipper club was also raided by the rioters.

The Police, the British Forces and Volunteer Defence Force have been on duty almost unceasingly since yesterday and have acted admirably in a difficult situation. This morning they were reinforced by additional forces from outside the Colony.

Riot in East Shirley Street

Two truckloads of rioters proceeding east along East Shirley St. early this morning were stopped in the vicinity of William and Fowler Streets by the British Forces. A disturbance caused and lasted for about an hour the men being divided and after some further time dispersed.

Two of the Cole-Thompson pharmacies, one in Grant’s Town and the other in East Shirley Street, were the object of attack by rioters. The contents of both stores were completely looted and what was not desired was wantonly destroyed. Large stocks were carried at both stores and a considerable quantity of essential drugs and medicaments, which may be extremely difficult to replace in present conditions, were scattered to the winds. Several liquor stores were damaged.

A number of casualties have been reported but no official statement has been made on this subject.

Two of the Cole-Thompson pharmacies, one in Grant’s Town and the other in East Shirley Street, were the object of attack by rioters. The contents of both stores were completely looted and what was not desired was wantonly destroyed. Large stocks were carried at both stores and a considerable quantity of essential drugs and medicaments, which may be extremely difficult to replace in present conditions, were scattered to the winds. Several liquor stores were damaged.

A number of casualties have been reported but no official statement has been made on this subject.

Some Loot Recovered

During the day further loot was recovered both in New Providence and from small boats about to leave the harbor, and arrests were being made throughout the day.

The Magistrate’s Court was not in session today.

The City

Bay Street presented a mournful picture to-day, reminiscent of the aftermath of a hurricane. Practically every window was covered with wooden shutters and many shops were closed entirely but food and other essentials were obtainable. The Royal Bank of Canada, which did not open yesterday, carried on a restricted business to-day…

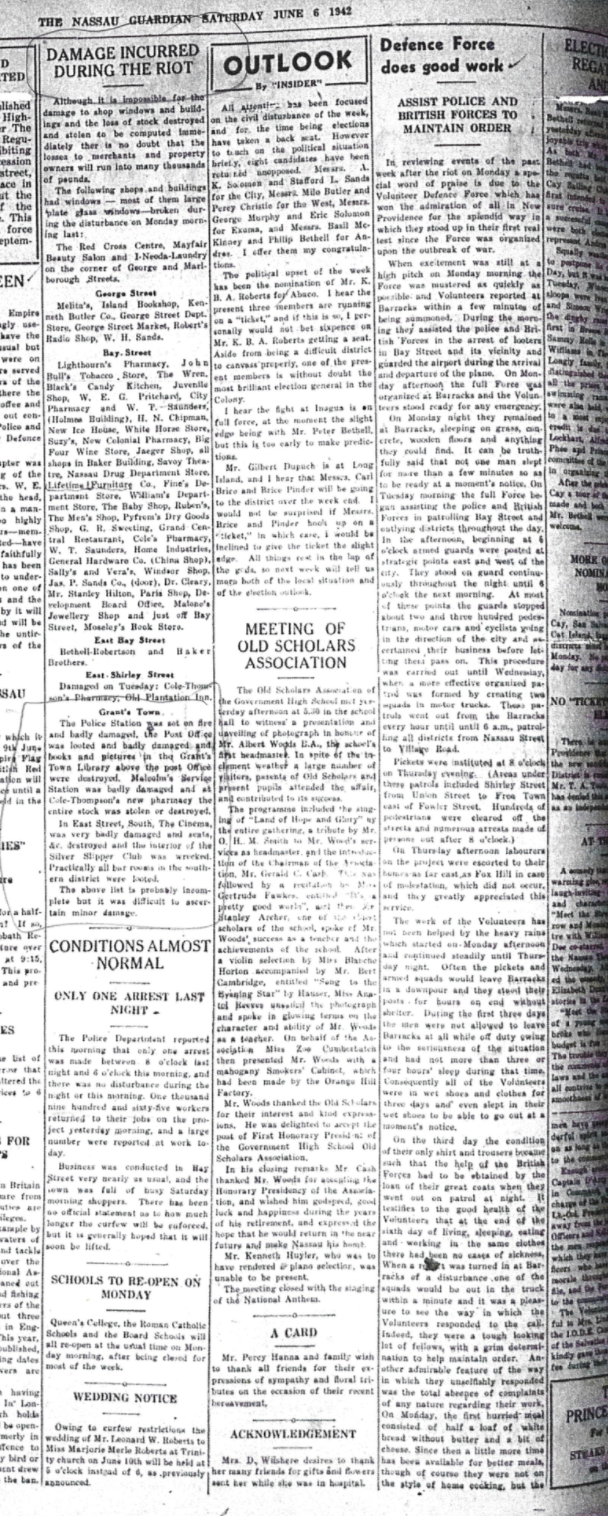

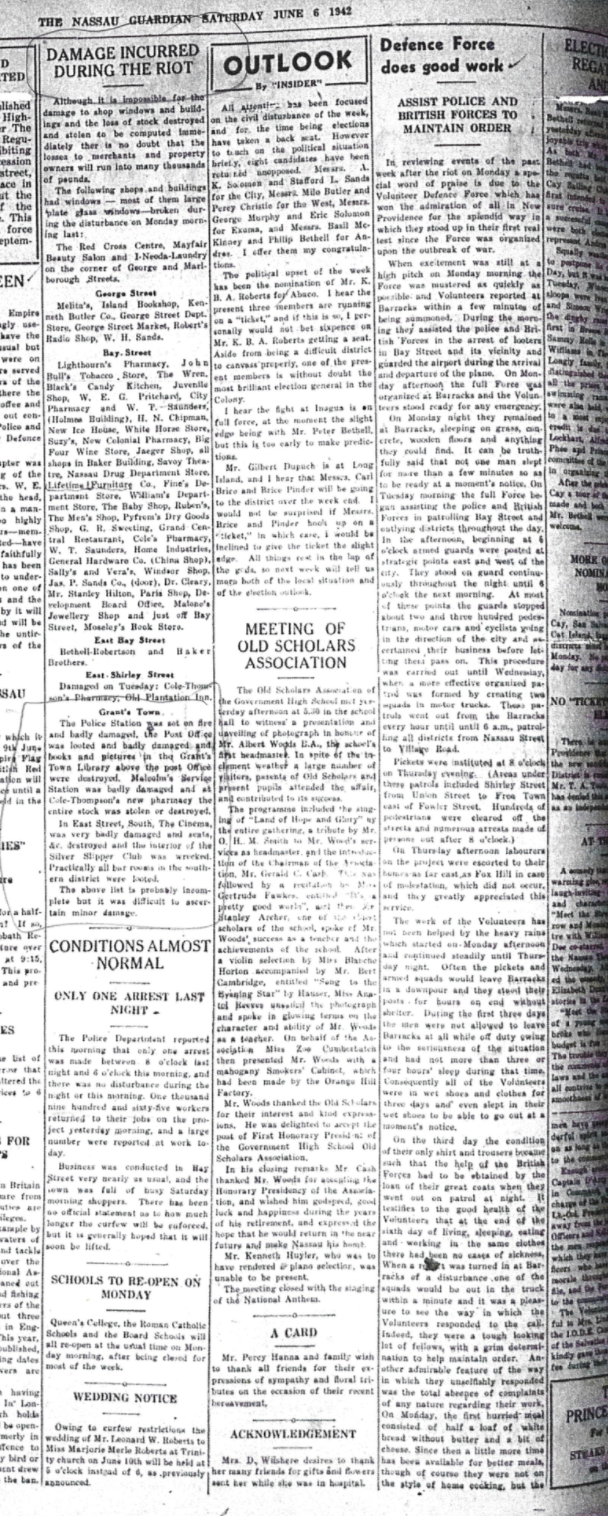

“Damage Incurred During the Riot.” Nassau Guardian, June 6, 1942. Page 2.

DAMAGE INCURRED DURING THE RIOT

…The following shops and buildings had windows – most of them large plate glass windows – broken during the disturbance on Monday morning last:

The Red Cross Centre, Mayfair Beauty Salon and I-Needa-Laundry on the corner of George and Marborough Streets.

George Street

Melita’s Island Bookshop, Kenneth Butler Co., George Street Dept. Store, George Street Market, Robert’s Radio Shop, W.H. Sands.

Bay Street

Lightbourn’s Pharmacy, John Bull’s Tobacco Store, The Wren. Black’s Candy Kitchen, Juvenile Shop, W.E.G. Pritchard, City Pharmacy and W.P. Saunders, (Holmes Building), H.N. Chipman, New Ice House, White Horse Store, Sury’s, New Colonial Pharmacy, Big Four Wine Store, Jaeger Shop, all shops in Baker Building, Savoy Theatre, Nassau Drug Department Store, Lifetime Furniture Co., Fine’s Department Store, William’s Department Store, The Baby Shop, Ruben’s, The Men’s Shop, Pyform’s Dry Goods Shop, G.R. Sweeting, Grand Central Restaurant, Cole’s Pharmacy, W.T. Saunders, Home Industries, General Hardware Co. (China Shop), Sally’s and Vera’s, Windor Shop, Jas. P. Sands Co., (door), Dr. Cleary, Mr. Stanley Hilton, Paris Shop, Development Board Office, Malone’s Jewellery shop, and Just off Bay Street, Moseley’s Book Store.

East Bay Street

Bethell-Robertson and Baker Brothers.

East Shirley Street

Damaged on Tuesday; Cole-Thompson’s Pharmacy, Old Plantation Inn.

Grant’s Town

The Police Station was set on fire and badly damaged, the Post Office was looted and badly damaged and books and pictures in the Grant’s Town Library above the post office were destroyed. Malcolm’s Service Station was badly damaged and at Cole-Thompson’s new pharmacy the entire stock was stolen or destroyed.

In East Street, South, The Cinema, was very badly damaged and seats, &c. destroyed and the interior of the Silver Slipper Club was wrecked. Practically all bar rooms in the Southern district were looted.

The above list is probably incomplete, but it was difficult to ascertain minor damage.

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.

“Government announces situation now at hand.” Nassau Guardian, June 2, 1942. Pages 1-2.